The Final Chapter - The Giblin Brothers and Their Circle of Crime

- Andy Yarwood

- Mar 30, 2025

- 16 min read

One winter’s day, six poorly dressed boys, battered and broken, the youngest barely ten, stepped off a Midland Railway train at Shustoke station. Under the watchful gaze of a stern Labour Master, they were led into unfamiliar Warwickshire. These boys, waifs from Birmingham’s slums, trudged two miles along a quiet, isolated lane under his strict supervision.

The treatment of children by the justice system in the 19th Century was harsh and deeply cruel. Before the mid-19th century, children were frequently imprisoned alongside vicious adult criminals, viewed as inherently flawed, and described as "hardened criminals" even when their “crimes” were minor. In 1811 they were often sentenced to death for petty offences.

From a young age, many children feel a strong urge to steal. In the country, such temptations are largely confined to pilfering from apple trees. However, in towns, the range of opportunities is far greater. In the countryside, the child is often under the watchful gaze of neighbours, with their actions closely observed and judged by the community. In contrast, a child in the city can commit numerous offences before attracting the attention of his fellow citizens.

A high mortality rate, overcrowded and grim back-to-back housing, the early loss of one or both parents and extreme poverty were the realities of life for children. When parents do survive, they frequently become drained of energy and lapse into a persistent state of indifference. Unsurprisingly, children growing up in such conditions face a relentless battle to survive.

Education is often regarded merely as a necessity for younger children who are too small to contribute to the family income through work. For older children, however, not only is schooling seldom encouraged, but it is frequently looked down upon and avoided whenever possible. In some cases, parents repeatedly move houses to evade attendance officers. Even when parents wish for their children to attend school, the extreme poverty of the household often compels the children to assist their mothers with poorly paid work in their spare time. It is little wonder, then, that many children attending school fall below average in basic education. While their intellectual progress may be limited, their misdirected energies often lead to an early involvement in delinquent behaviour. Boys and girls as old as 12 or 14 can sometimes be found struggling to form letters and spell basic words, seated alongside much younger children of 7 or 8. (75)

Mary Carpenter, a leading reformer, championed approaches centred on nurture and education. She criticised the prison system for turning children into "good prisoners" rather than rehabilitating them. Her observations highlighted the grim reality: once children entered prison, they were likely to return repeatedly, their spirits broken and futures irrevocably damaged.

The destination for our six young boys at Shustoke station was the Shawberries, a country house set within 45 acres, newly leased by Birmingham Borough Council for £130 annually. The date was 28 March 1868. These six young boys were about to make history as the first residents of the first industrial school in the country established by a local authority. (76)

Industrial and Reformatory Schools

In 1854 the Reformatory School Act was passed. The term "Reformatory School" refers to an institution designed to provide industrial training for young offenders. Within these schools, offenders are housed, clothed, fed, and educated. Similarly, the term "Industrial School" describes a facility focused on industrial training for children, where they are also accommodated, clothed, fed, and taught.

Young offenders aged between 12 and 16 may be sent to a Reformatory School if they are convicted of an offence that would result in imprisonment or penal servitude for an adult.

The ideas of an Industrial School appear to have originated in Scotland, the first being established there in 1850. In contrast to a Reformatory School, the scope of children eligible for Industrial Schools was broader, encompassing six distinct categories.

Begging or wandering, or are the children of tramps and ne'er-do-weels,

Children who have committed offences which in the case of an adult would be punishable with imprisonment or penal servitude.

Children who are unmanageable in their own homes,

Children who fail to attend school regularly

Children who are taken from immoral surroundings.

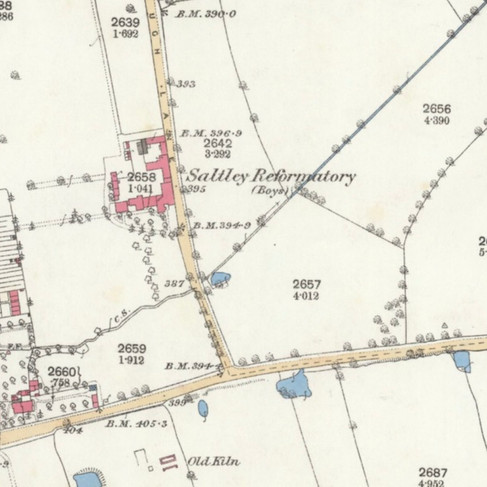

These institutions sought to strike a balance between education and punishment. The Saltley Reformatory, founded in 1852 by Joseph Sturge and Charles Adderley, the Shustoke Industrial School, opened in 1868, and the Gem Street Industrial School, established in 1846 became pivotal in providing vocational training and discipline to boys from impoverished or criminal backgrounds.

These schools aimed to reform through strict routines: early morning wake-ups, hours of labour, and limited recreation. At Shustoke, boys worked on a farm, attended evening school, and lived under the watchful eyes of their masters. Although these institutions were an improvement over prison, they were far from idyllic. Overcrowded dormitories, inadequate hygiene facilities, and a lack of personal freedoms were frequent criticisms.

Committees composed of magistrates, doctors, clergymen, retired military and naval officers, and county or city magnates attended annually to report on the ongoing conditions of the schools. Their findings are highlighted in the Birmingham Daily Post.

Birmingham Daily Post - Thursday 25 April 1889

“The annual meeting of the Saltley Reformatory Institution celebrated its continued success-841 boys had been received at Saltley. During the last three years, 93 boys had been discharged, of whom 83 were now leading honest lives. Only seven had relapsed into crime, and been reconvicted”.

“premises in thoroughly good order; health. And general condition very good; educational state very satisfactory, the boys throughout the school being thoroughly well-taught, and appear to take an interest in their instruction. Industrial training includes farm work, gardening, and tailoring. And shoemaking, all well attended to. Average”

The reality in my mind was far from the truth with zero understating of the young children who committed these offences and why they committed them. The life of the Giblin brothers and their friends tells a far different story. Could it not be that their life of crime can be brought back to their time as adolescents and repeatedly thrown into Prison initially and then these Reformatory schools?

The committee even remarked that “there was very little room for a possible feeling of jealousy on the part of honest working people that the Reformatory boy had a better start in life than their own child…The plan of governing the school by kindness instead of through dread of punishment reflected great credit -

Kindness?”

Many school managers, during their visits, appreciated that boys give a sharp salute, girls pause their activities, and all pupils stand swiftly to greet them with a unified "Good afternoon, ma'am" or "Good morning, sir," depending on the time of day. However, there is little indication that they attempt to engage with the students on a genuine or meaningful level.

Classroom walls are frequently dull and sombre, often lacking any decorations beyond illustrations cut from newspapers, which are usually either irrelevant or uninspiring. These spaces rarely feel inviting or homely, and opportunities for students to experience the satisfaction of personal ownership are minimal.

In the dormitories, overcrowding is common, and the washing facilities are often inadequate. Lavatories are typically damp and poorly lit, with unsatisfactory designs for sinks and baths. Towels left in a grimy state.

There was a tendency among managers not to "spoil" the children, (77)

Gem Street Industrial School Saltley Reformatory School, was situated on Fordrough Lane

Little More than Penal Education

The treatment of children from impoverished backgrounds in 19th-century Birmingham’s reformatory and industrial schools reveals stark contrasts in how the establishment viewed delinquency among the lower classes versus wealthier families. Rather than addressing the underlying causes of poverty and social deprivation, authorities often removed children from their families, believing their waywardness stemmed from parental failure rather than the hardships of slum life. This approach echoes contemporary concerns over the treatment of disadvantaged youth today.

The line between punishment and education was often blurred in these schools. Critics argued that children committed to gaol for reasons as simple as truancy, begging, or 'immoral surroundings' received what amounted to a 'penal education.' Many came from homes marred by poverty, neglect, or alcoholism—problems society seemed content to blame solely on the parents while doing little to address root causes like squalid housing or exploitative labour.

Some in the establishment viewed the “working classes’ with utter contempt:

“Look at them in the streets, where, to the eye of the worldly man, they all appear the scum of the populace, fit only to be swept as vermin from the face of the earth ;—see them in their homes, if such they have, squalid, filthy, vicious, or pining and wretched with none to help, destined only, it would seem, to be carried off by some beneficent pestilence ;—and you have no hesitation in acknowledging that these are indeed dangerous and perishing classes”

Some individuals saw the plight of these children who did not attend school roaming the back streets or working in the sweatshops

A teachers Journal

* * *As I went to School one morning I met a miserable little boy crying ; he said he felt ill from want of food, but that his mother beat him out of the house ta go and sell oranges. I took him to the School, gave him some food, and promised to buy all his oranges, and to give-him his dinner regularly, if he would come every day. The master called on his mother to induce her to agree to this, but quite ineffectually ; the neighbours said that she made this poor little fellow and his twin brother support her. I now see them in the streets idle and ragged, but can do nothing. (78)

When confronted, they would openly admit that they could provide better support for themselves and their parents through theft than through honest work.

One evening a boy came to the School looking more like a scarecrow, in dress and appearance, than anything else. The boys cried out that he was Irish, (many of them were really so themselves) but he indignantly asserted that he was as good an Englishman as any one of them! (5)

Relationships and Bonds

A child might be entirely innocent of any wrongdoing. Many are arrested simply for being found wandering or for very minor offences such as stealing an apple, butter or handkerchiefs are held in prison with hardened and habitual criminals, of all kinds and ages while awaiting trial.

The authority's procedure for dealing with a child offender was to; dismiss the case, put in care of a relative, Industrial School; or Reformatory School, whipping, pay a fine, place of detention.

After reviewing hundreds of criminal registers, it was rare for a child’s case to result in acquittal. For the children who were living on Livery Street and the surrounding streets, the outcome was often one of the last four options.

If a fine was imposed and could not be paid, the child would be sent to prison. For children under 14, the law required the fine to be paid by their parents. However, if the father squandered his earnings on beer, the family was destitute, or there were no Parents, it’s easy to see how a revolving door of criminality and imprisonment became an inevitable future for these children.

The notion of a child being inherently abnormal and of a criminal mind is flawed. Most children do not wish to act wrongly, a young person of 9 or 10 or 11 is placed in an environment completely at odds with their natural instincts. Where they are not permitted to raise their voice in the loud and cheerful manner that is essential to their nature. The prison or reformatory school walls are thick, the noise of other inmates reverberating around, and the keys to lock them are loud, weighty and ponderous.

Their social interactions are entirely restricted, with no words of kindness or affection reaching them. A lively boy, who might be moved to tears by the reformatory school’s stern military governor or the prison guard, even worse whipping. Instead, channel their energy into acts of mischief within the confines of the prison cell. If they learn anything, it is only how to behave as a compliant prisoner.

Entering as a child and if declared innocent, they would leave with little of their innocence intact after enduring the prison environment. They were simply thrown back onto the streets even less prepared to navigate it effectively, embittered and with no self-respect. If found guilty, they would return to prison, where they were exposed to every vice and depravity such a place could foster, effectively shaping them into the criminals they were accused of being.

" it ain't that, but I don't want to be bad, and when other boys go on a spree, I just can't help going too and doing my bit." (79)

In her publication in 1877 on Reformatory Schools 1877 Mary Carpenter wrote of her experience of visiting various gaols and reformatory schools in Bristol.

“The officials were unanimous in their belief that once a boy enters the system, he is almost certain to return repeatedly until he faces transportation. Of all the boys and girls I spoke to, only one or two were first-time offenders; most had been there five or six times, with one boy having been detained 16 times.

There were girls who bore the visible marks of a life of crime, including a little girl of just 12 years old who was already a habitual pickpocket. They all seemed penitent, vowing that this would be their last offense. Despite having homes, most had received little to no schooling outside of what they were taught in prison. The matron remarked that for many of these children, prison felt like their only real home.

We walked through long corridors of cells, each opened as we passed. At the entrance of each cell stood a youth or man, some dressed in red to indicate they were sentenced to transportation, while others wore badges displaying the number of their convictions.

The prisoners engaged in monotonous tasks, such as picking oakum, which seemed likely to foster despair and brooding over their grim futures. It was a stark contrast to the lively atmosphere of a good Free School. Boys attended classes in shifts—half in the morning, the other half in the afternoon—while the rest of their time was spent on industrial work. According to the master, only about one-third of the boys could read when they arrived, and fewer than one-tenth could find any enjoyment in reading. Many appeared to view school as a way to escape work rather than an opportunity to improve themselves. Some, however, did make progress.

We later encountered two boys crying bitterly in a dark cell. Solitary confinement with a bread-and-water diet was usually deemed sufficient punishment, and flogging was rarely used, reserved only for severe insubordination. However, juvenile prisoners often faced corporal punishment as part of their sentences. Some whippings were so brutal that they elicited screams of agony from the young offenders and tearful pleas from their companions for mercy. Even the turnkeys expressed heartfelt pity.

Juvenile offenders were subjected to harsher treatment compared to adult prisoners. Older culprits, though more culpable, did not face whipping for larceny, a punishment frequently inflicted on younger inmates.

At Pentonville Prison, 70 to 80 boys—some as young as 10 or 11—were initially kept in strict solitary confinement. However, this led to severe consequences: debility, joint contractions, signs of sluggishness, and mental decline. Concerned for their well-being, the authorities eventually adjusted the regimen, allowing the boys to work in the garden instead of engaging in sedentary tasks like picking oakum and wool”

Summary: The Institutional Response to Juvenile Delinquency in Birmingham

The institutional response to juvenile delinquency in Birmingham during the late 19th century, drawing on contemporary newspaper reports to highlight the prevailing attitudes towards working-class youth. Rather than addressing the root causes of crime—poverty, overcrowding, and lack of education—authorities saw working-class children as inherently wayward and blamed their parents for negligence, rather than acknowledging the role of poverty and slum conditions in shaping their behavior.

The justice system overwhelmingly favoured a punitive approach, prioritising imprisonment and institutionalisation over prevention or support.

Institutional Attitudes Towards Poor Children

The system viewed parents as irresponsible and actively sought to remove children from their family units. "For the first time, the parents of erring children were made to feel the responsibilities which they had hitherto slighted, or—to put it more strongly—altogether shirked."

Authorities believed state intervention was necessary to prevent the development of a "criminal class," positioning the law as a strict parental figure.

Aid was often withheld from destitute children unless they had committed a crime, reinforcing a punitive approach to poverty rather than a supportive one.

Children sent to reformatories were often assumed to be future criminals, leading to an inflexible and discriminatory approach to juvenile justice.

Harsh Treatment of Child Offenders

Before being sent to a reformatory, children were required to serve a short prison sentence to

"blot out all trace of sickly sentiment" in their treatment.

There was a clear divide between those seen as "apprenticed to crime" and those who were merely victims of circumstance, with a preference for short, sharp punishments for younger first-time offenders.

Authorities believed that reformatories should focus on moral discipline rather than education, ensuring that children left with the ability to resist future temptations.

The Role of Emigration in Removing ‘Wayward Youth’

Another controversial aspect of the reformatory system was the practice of sending boys abroad upon discharge. The Birmingham Daily Post (Thursday, 25 April 1889) reported that:

"About one-third of the boys discharged over the last three years had been sent abroad... Parents had to give permission for their sons to be sent abroad, and employment was arranged for them in the colonies."

This practice was framed as an opportunity to remove boys from their "old associations" and give them a fresh start. In reality, it was another way to rid Britain of its poor, ensuring they would not return to crime in their hometowns

Reformatory Schools: A Mixed Success

Reports from institutions like Saltley Reformatory and the Birmingham Reformatory Institution show that while some boys successfully reintegrated into society, a significant portion reoffended.

The Birmingham Daily Gazette (Thursday, 18 October 1877) reported that at the Saltley Reformatory Institution, 74% of boys discharged between 1873–1875 were considered successfully rehabilitated, yet 12 had reoffended and nine had disappeared.

Industrial training, such as farming, tailoring, and shoemaking, was a core aspect of reformatories, designed to provide boys with employable skills.

There was a strong push to prevent children under 14 from being sent to prison before entering a reformatory, reflecting a gradual shift towards a more rehabilitative approach.

Despite efforts to reform children, many were released back into the same poverty-stricken environments that had led them into crime in the first place, limiting long-term success.

Conclusion

These reports illustrate how institutional attitudes towards working-class children were deeply rooted in class prejudice. Rather than addressing the root causes of poverty and neglect, the system blamed parents and sought to discipline children through incarceration and strict institutional control. While reformatory schools provided some level of rehabilitation, they were still driven by the belief that working-class children were inherently criminal unless reformed. The reluctance to support poor children unless they had committed a crime reveals an enduring issue—one that remains relevant in discussions about poverty and juvenile justice today.

From the Reformatory Schools to the Streets of Snow Hill

In the late 19th century, Birmingham’s slogging gangs emerged from a mix of poverty, and overcrowding. Deeply rooted in the working-class districts of Birmingham, these youth gangs, often made up of teenage boys and young men, engaged in street violence, territorial fights, and clashes with the police. Children saw the gangs as a source of identity, protection, and social status often as a way to assert dominance and gain local notoriety. (See my earlier blog that explores this in more detail).

My research reveals that a significant proportion of children sent to gaol or reformatory schools were of Irish descent or beggars. Mary Carpenter noted that 95 out of 271 children from the streets ended up in the gaol or police office. She acknowledged that reformatory schools did little more than train boys to be obedient prisoners. Once they entered the system, few ever truly escaped it.

The Giblin brothers and their associates were no exception.

The Giblin Slogging Gang - Accomplices, friends, brothers & sisters - click here to see a visual representation of family connections

The Giblin Slogging Gang and their group of friends all lived in the streets surrounding the Gun Quarter; settling in Livery Street, Water Street, Northwood Street, Hospital Street, Snow Hill or St George Street. Many of their parents had already established deep social and familial ties, primarily originating from County Mayo and Roscommon in Ireland. These connections were forged long before their arrival in Birmingham, a shared experience of their rural life in Ireland and the devastating effects of the Great Famine. The task of pinpointing exact relationships between individuals within these families, however, is fraught with difficulty.

Family connections were often ambiguous due to a combination of factors. Addresses and ages were frequently altered— sometimes dramatically—either to secure employment, enlist in the military, or avoid legal repercussions. Surnames, too, were subject to change—variations in spelling, Anglicisation's, or deliberate changes to avoid detection were not uncommon. In some cases, previous marriages and the birth of children further complicated family structures, making it difficult to establish definitive parentage.

While the children themselves were born in Birmingham, their parents immigrated to the UK in the early to mid-19th century. The extended family connections—possibly brothers, uncles, aunts, or grandparents—meant that a child might initially live with a relative. However, repeated incarceration in gaol or placement in reformatory schools often left these children living on the streets or moving between the homes of friends.

Despite this, certain family names consistently appear intertwined—not only through marriage and shared occupations but also through patterns of residence. Many of these families lived on the same streets, often within the same courts, sometimes next door to one another. Over decades, these connections persisted, with one family occupying an address in one decade, only for another related family to be found at the same location twenty or thirty years later. These patterns suggest a strong sense of community, mutual support, and possibly informal networks of housing within the Irish immigrant population in Birmingham.

These streets belonged to families like the Feeneys, Cains, Morans, Prendergasts, and Welches—families whose names filled the police records and criminal registers, and whose sons grew up side by side with the Giblins, in the same courts, attending the same schools, serving time in the same prison cells.

For those who could not escape the streets, the options were limited. A few found work in brass foundries, button-making factories, and ironworks, but many more found their way into gangs, street fights, and the magistrates' court. They were battlegrounds, where boys learned to use their fists before they learned to read.

By the time John and Thomas Giblin reached their teenage years, Birmingham’s industrial slums had already shaped them into fighters, survivors, and criminals in the making. For the Giblin brothers and their friends, crime was not just about money—it was about survival, status, and power. The first offence was often petty theft or stone-throwing, but by the time a boy reached fifteen, he had already been whipped, locked up, and labelled a menace by the courts.

The Streets That Shaped the Giblins

To outsiders, the streets around Snow Hill seemed like a place where men worked hard, drank harder, and died young. But for those who lived there, it was a world built on loyalty, family ties, and a strict code of respect.

The police patrolling Kenyon Street Station knew these families by name. They knew where they lived. They knew that after dark, certain alleys were lost to the gangs.

🔹 Livery Street—where drunken fights spilt out of taverns, where Tommy Giblin’s name became feared among the sloggers.

🔹 Water Street—where John Giblin built his reputation as a gang leader, his name filling crime reports for robbery and street violence.

🔹 Hospital Street—where mothers and sisters worked themselves to exhaustion, doing laundry, sewing, and piecework to survive, while their sons were sent to prison for stealing bread.

🔹 Snow Hill—where the Irish immigrant families of Birmingham lived stacked upon one another in crumbling courts, their lives bound together by shared poverty and shared crime.

In this world, friends became accomplices, brothers became gang leaders, and survival meant standing your ground in the streets and in the dock.

The Giblin brothers and their associates—the Feeneys, Morans, Prendergasts, and Welches—were the rulers of these streets.

They did not just commit crimes; they owned the violence.

To the magistrates, they were a plague.

To the police, they were in a constant fight.

To the boys growing up in their shadow, they were legends.

And yet, despite all their power in the backstreets, despite their brutal reputation, none of them ever truly escaped.

The Families of the Giblin Slogging Gang (1861–1881)

This map highlights the residences of families connected to the Giblin-led Slogging Gang between 1861 and 1881.

The key on the map and the list below shows and highlights just how many children from these families were sent to Industrial or Reformatory Schools.

This network of families helped the gang gain influence in Birmingham’s slum areas. It also shows how poverty and hardship led multiple generations into a cycle of crime and being sent to institutions.

What Comes Next?

The following chapters trace the lives of these families, each one playing its role in the rise and fall of the Giblin's.

From William Bates, who fought alongside them, to Catherine Moran, who was swept up in their crimes, to the Feeneys, Cains, Welch's and Prendergast's, whose fates were forever tied to the gang—this is the story of a generation raised in the slums, condemned from the start, and defined by the streets they could never leave.

And at the heart of it all, the two men who would shape this world the most—John and Thomas Giblin.

Comments